Misdiagnosis: why we must not turn our back on graduate-only entry to nursing

In a recent blog on rcni.com, chief executive of Healthcare Management Solutions Tony Stein identified the changing level of nurses’ education when they qualify as the ‘root cause’ behind the current nursing workforce crisis. This is a serious misdiagnosis.

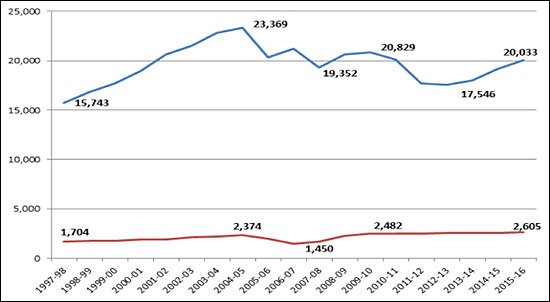

Mr Stein’s explanation runs something like this: degree-level education means that some people with a genuine desire and capability to nurse, particularly those who are older, are not able to do so. The problem with this theory is that the low number of new ‘home-grown’ registered nurses coming into the workforce has nothing to do with the level of education but is a direct result of deep, affordability-driven cuts to the number of nursing education places between 2004 and 2012 (see graph below) and nothing to do with the level of education.

Given the lag time for education, we are now experiencing the ‘output’ from the lowest commissioning figures for a decade. It is hardly surprising that there is a shortage of nurses, but whether or not they have degrees is a red herring.

Total numbers of commissioned nursing (all fields) and midwifery pre-registration education places in England by year, 1997 – present, from Hansard 2012 and HEE workforce plans.

Total numbers of commissioned nursing (all fields) and midwifery pre-registration education places in England by year, 1997 – present, from Hansard 2012 and HEE workforce plans.

So how about evidence for his other arguments, namely that nursing courses are now dominated by young applicants and that attrition is sky high? Neither of these stack up. UCAS data from 2014 shows that 61% of students accepting a nursing place in the UK were over age 21. Across all courses, only 22% were mature students.

Claiming that 40% of nursing students drop out in the first year is simply wrong. Higher Education Funding Council for England data for nursing shows a 90% continuation rate from year of entry to the following year. Attrition rates in other parts of the UK are also at their lowest levels for ten years.

There is some truth in identifying barriers for existing healthcare staff who have wanted to become registered nurses but have found the system stacked against them, either because they haven’t had support to gain the qualifications they need or because pathways from one qualification to another have been unclear.

Work is underway across the UK to clarify routes into education and create new avenues of support from employers. The long-standing range of entry routes into nursing programmes, whether this is access courses, higher national diplomas or foundation degrees, are all part of this. But this is neither quick nor cheap, since many of these students complete the course part time and need salary support while they do it.

So that's the root cause, what about the future? Tony Stein’s main argument is that to deal with the staffing crisis there needs to be a reintroduction of the state enrolled nurse (SEN). This is hardly a new argument, but it risks understating the vital and often undervalued roles in nursing care already played by healthcare assistants, assistant practitioners and others. There is a strong case for making these roles more consistent in terms of education, roles and responsibilities, even regulation, but to confuse this with the role and education of registered nurses is a mistake.

The assumption that underpins this - that the role of a registered nurse can be reduced to a set of tasks - misunderstands what it is to be a nurse: the knowledge, skills and critical thinking to know not just what you are doing, but why. To understand when something can be safely delegated to another member of the team and when it cannot; to be able to work with patients and families as partners rather than just recipients of care; to know and be able to apply the evidence base for safe, effective practice; to be able to work autonomously across a range of settings but know the boundaries of your own scope of practice.

We don’t yet have as much data for the impact of degree-level nursing in care homes or in the community, but we do have it for hospitals. Evidence from the RN4CAST study of nine countries, including England, published in the Lancet last year, showed that a 10% increase in the proportion of nurses holding a bachelor’s degree is associated with a 7% decrease in the risk of death after surgery.

Education is not an expensive luxury but a vital foundation of safe patient care. Given that increased registered nurse staffing was the second factor associated with lower mortality rates in the Lancet study, undermining degree-level education at a time when nurse staffing levels are a challenge would be exactly the wrong response.

So where does this take us? When you look at the data, it is clear that the current nursing staffing crisis has been building for ten years, and it will probably take another ten years to resolve.

There are no simple solutions or quick fixes, but seeking to downgrade education for registered nurses is an unhelpful distraction. As services come under increasing pressure, they will need intelligent, highly expert registered nurses more than ever.

About the author

Lizzie Jelfs is director of the Council of Deans of Health which represents the UK’s university faculties engaged in nursing, midwifery and allied health professional education and research.

Lizzie Jelfs is director of the Council of Deans of Health which represents the UK’s university faculties engaged in nursing, midwifery and allied health professional education and research.

@councilofdeans

Contact us

Do you feel strongly about this issue? Email your thoughts to letters@rcni.com or contact us via Facebook or Twitter